Endometriosis

What is it?

Endometriosis is described as the presence of endometrial tissue in locations outside the endometrial (uterine) cavity.

Endometriosis is commonly found in the cul-de-sac (behind the uterus), the rectovaginal septum (the tissue between the rectum and vagina), on the surface of the rectum, the fallopian tubes and ovaries, the uterosacral ligaments, the bladder, and the pelvic side wall.

Generally endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum is more likely to deeply invade the underlying structures.

Is endometriosis a genetic disease?

Studies have shown that sisters have a six times increased risk compared to their husband's sisters. Other studies show up to an eight times increased risk when compared to other women.

How common is it?

Between 25-50% of infertile women have been reported to have endometriosis. Endometriosis affects 5 million U.S. women, approximately 6-7% of all females.

What are the causes?

No one theory seems to explain all cases. Several theories, however, have been postulated.

Commonly during the menstrual period, endometrial cells can be found in the fluid behind the uterus. The most widely held theory, retrograde menstruation, states that endometriosis occurs when endometrial fragments attach to nearby pelvic structures and grow. Other theories include tissue transplantation, induction of changes in peritoneal lining cells, spread through uterine veins, and direct extension through the lymphatic system.

How Does Endometriosis Cause Fertility Problems?

In cases where there is obvious disruption of the normal anatomy, endometriosis is a known cause of fertility problems. In fact 30-40% of patients with endometriosis are infertile. This is two to three times the rate of infertility in the general population.

In patients with endometriosis, the monthly fecundity (chance of getting pregnant) decreases by 12-36%. However, the long term cumulative pregnancy rates are normal in patients with minimal endometriosis and normal anatomy. Studies provide contradicting information, but the bulk of research at this time indicates that pregnancy rates are not improved by treating minimal endometriosis.

Under the influence of cycling female hormones, each month the displaced endometrial tissue grows and sheds blood at the time of menses. Instead of flowing harmlessly outside the body, however, the excrement wreaks havoc in the abdominal cavity.

The resulting chronic tissue inflammation leads to the formation of adhesions and scars, which surround and entrap delicate reproductive organs. The adhesions can be so extensive that they literally freeze the tubes, ovaries, and uterus into place (stages III and IV). The eggs themselves are trapped in the heavy shrouds of scar tissue surrounding the ovaries, and infertility results. As the disease spreads, the older endometrial cells burn out, leaving dead scar tissue in their wake.

Even mild forms of the disease (stages I and II) may interfere with fertility. It is hypothesized that the prostaglandins (hormones) secreted by the active, young endometrial implants or other chemicals secreted by white blood cells may interfere with the reproductive organs by causing muscular contractions or spasms. The tube may be unable to pick up the egg, and the stimulated uterus may reject implantation. In addition, sperm motility may be adversely affected along with the ability of the sperm to penetrate into the egg. Although the mechanisms are not fully understood, endometriosis may also result in anovulation (17 percent), cause a luteal phase defect interfering with implantation, or cause a luteinized unruptured follicle.

Some researchers suggest that the woman's body may form antibodies against the misplaced endometrial tissue. The same antibodies may attack the uterine lining and cause the high spontaneous-abortion rate: up to three times the normal rate. (Fortunately, removing the endometriosis with medication or with surgery will reduce this risk to normal.)

The normal tissue surrounding the endometriosis implant becomes puckered and ischemic (suffering from lack of oxygen), causing pain similar to that from a heart attack. Attacked over a prolonged period, the fallopian tubes may become inflamed and swell shut. Blocked by adhesions, the tubes can no longer provide safe passage for egg, sperm, and embryo. Ectopic pregnancies become a real danger: up to sixteen times more likely than the normal population (16 percent vs. 1 percent).

What Are the Symptoms of Endometriosis?

Nearly one-third of the women having endometriosis have no symptoms other than infertility. The others have varying degrees of symptoms, depending on the stage of the disease. Oddly enough, the early stages or milder forms are frequently more painful than the later stages. We believe this is because the young endometrial tissue liberates spasm-causing prostaglandins, whereas the older endometrial tissue simply burns out and turns into inactive scar tissue. The most common symptoms associated with endometriosis are pain and infertility, however, premenstrual spotting, urinary urgency, rectal bleeding, painful urination, bloody cough, and skin nodules may also be noted.

Endometriosis may frequently mimic other disorders such as pelvic adhesions, dysmenorrhea (menstrual cramps), irritable bowel syndrome, colitis, and ulcer disease. Careful evaluation is necessary to ensure accurate diagnosis. Diarrhea or rectal bleeding and tenesmus (sense of rectal fullness) at the time of menses are particularly telling symptoms.

Diagnosing Endometriosis

Any complaint related to menses suggests endometriosis. Endometriosis associated with the classic symptoms of painful menstrual periods and/or painful sexual intercourse is relatively easy to diagnose. However, when the symptoms are less suggestive-unexplained infertility, irregular periods, or spotting, for example-identifying the disease may be more difficult. Occasionally while doing the pelvic examination I can feel the telltale beading on the outside of the reproductive organs. The only definitive diagnostic procedure for endometriosis, however, is a direct look inside the abdominal cavity and a biopsy of the tissue.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Since laparoscopy requires general anaesthesia, I try to rule out all other male and female fertility factors before performing it. Depending on the woman's age, history, and findings from the workup, however, I may choose a more aggressive diagnostic approach for a particular couple. If the woman is in her thirties and if she complains of pelvic pain or has unexplained infertility, I'm likely to perform a laparoscopy sooner.

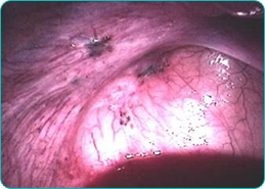

Viewed through the laparoscope, the endometrial lesions look like raised shaggy brown or blue-black areas ranging from 2 to 10 cm (1 to 4 inches) in diameter. If the disease has been present for a prolonged period of time, the tissue adjacent to the implants will pucker and burned-out areas will show fibrotic scars. Advanced endometriosis (stage III or IV) may invade, pucker, and erode the walls of affected organs, and adhesions may be so dense that they "freeze" the pelvic organs into distorted positions.

There is poor correlation between the degree of pain or infertility and the severity of disease. Early lesions which are clear or red are metabolically more active than older, dark, fibrotic lesions. This metabolic activity may be responsible for the associated infertility, immune abnormalities, urinary urgency, pelvic pain or diarrhoea.